The first part of this newsletter celebrates the centenary of the British Empire Exhibition held at Wembley Park in north London in 1924-25. Nowadays all things linked to colonialism and Empire are tainted due to our awareness of the realities of domination and exploitation. The exhibition, however, was a product of its age, part of our complex history, worthy of study rather than being ignored, to be understood in the context of its time. Max Gill, of course, was a man of this time. He would have been proud to be British and a member of the Empire, and he would also have been proud to be creating items for this magnificent exhibition.

Opened by George V on April 23rd, the exhibition was an extraordinary showcase of culture, crafts, commerce, technology, industry and produce from across the globe, with unusual and exciting exhibits including elephants, a Burmese temple, and even a butter sculpture of the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VIII). The event was organised in the post WW1 era by the British Government to demonstrate the economic might and global power of the Empire in the face of competition from other powers such as America, Germany and Japan and growing anti-colonial feeling. It ran for six months in 1924 and again in 1925, finally closing on 31 October by which time 25 million people had visited.

British Empire Exhibition 1924

Official guide with map

Most large British companies and organisations were keen to showcase their wares and services and commissioned the top architects and graphic artists to create eye-catching stalls and displays. In a letter written on April 20th 1924 Max Gill wrote to his brother Romney:

‘For the last two months I have been really very busy on sundry works for the Wembley Exhibition. Working on ‘the Pageant Book’, the Queen’s Doll’s House, Shell-Mex Co., Spillers and Staples. Much of the work meant decorative painting or map-making …’.

The Pageant of British Empire was a lavish spectacle which took place in the newly built Wembley Stadium over six wet weeks and over 30 performances with a cast of 15,000, along with 300 horses, 50 donkeys, 1000 doves, 72 monkeys, 7 elephants, 8 camels, and 3 bears. Its storyline celebrated imperial and military heroes, from Cabot to Nelson and depicted scenes illustrating life in all corners of the empire. The exhibition guide spoke of ‘an accent on inter-racial unity’ while the Prince of Wales, President of the Exhibition, wrote in his foreword that it was ‘a grand representation of all the nations under our flag’ and one which would ‘illustrate fully the economic resources of all our territories and peoples’.

The large (31 x 40 cm) Pageant of British Empire Souvenir Volume was illustrated with lithographic prints by Frank Brangwyn (who had designed the sets for the Pageant), and Spencer Pryse alongside patriotic poems by many of our greatest poets including Kipling, Wordsworth and Masefield. MacDonald Gill designed the covers as well as a striking centrefold map (60 x 40 cm) showing The World in the Time of Cabot. A particularly beautiful example of his craft, it portrays an unrolled scroll depicting known land in yellow encircling swirling seas of emerald and azure filled with colourful sea creatures and famous galleons being buffeted by the four winds. The discoveries of those early navigators John Cabot, his son Sebastian, Christopher Columbus and Vasco de Gama in the 15th and 16th centuries are documented in Max’s fine calligraphic hand and a vibrant compass at the bottom adds the final decorative touch. The pen-and-ink artwork together with the hand-coloured version of the map were donated to the V&A which selected the latter as its ‘Masterpiece of the Week’ for 7th February 1935.

The World in the Time of Cabot, 1924

The Queen’s Dolls’ House was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens and was – as Max put it:

‘a house in miniature – ⅟12 full size … ‘a wonderful creation … of which I, with some 2000 others, have been invited to elaborate, (my own work actually being – decoration and coats-of-arms in 5 of the room-lets, drawing for the portfolio (one of 200) – and the general ‘Entrance ticket to view same’, at Wembley)’.

He took his youngest brother to see it at Lutyens’ office; Cecil declared that ‘its [sic]really great fun – from the electric lights in each room, with switches the size of a pin’s head – to the bottles of Bass in the cellars ¾” long and full of beer!’.

The drawing Max mentions was a tiny watercolour measuring just 3.9 x 2.8 cm. entitled ‘The Fairy Dolls’ House’. This was to be kept with many others – by artists including Paul Nash, Helen Allingham, and William Nicholson – in the library drawers of the Dolls’ House. Max also designed the entrance ticket (artwork below) for the exhibit which was to be displayed in its own pavilion in the Palace of Art. It is now on public display at Windsor Castle.

Max’s design for Shell-Mex stood in one corner of the firm’s stall in the Palace of Industry which housed displays on railways, shipbuilding, motor cars and wireless. He described it as:

‘a 12′ by 7’ [3.7 x 2.1 m] oval modelled and painted map of the world, around which, by electricity, run 28 carved & painted models of ‘things in which petrol spirit is used’, the whole encased by a blue fibrous-plaster case-dome ‘studdied [sic] with electric stars etc.’.

The image shown here is Max’s own photo of the oval plaster map still in the studio and before the addition of the models although I believe a photo of the complete exhibit was published in the June 1924 issue of Commercial Art.

Map of the World for Shell-Mex, 1924

Plaster

For the stand of Spillers, the grain and milling firm (for which my grandfather Evan Gill – worked), Max

‘painted – on canvas – an 11′ x 7′ [3.36 x 2.13 m] map of Great Britain showing all the milling etc. centres and foreign trade. Quite a big thing to paint vertically, when my room at West Lodge [his home in Chichester] … is but 10′ 6″ high [3.2 m)’.

What happened to this map after the exhibition is a mystery and I have never come across even a photo. We only know of its existence from the letter Max wrote his brother.

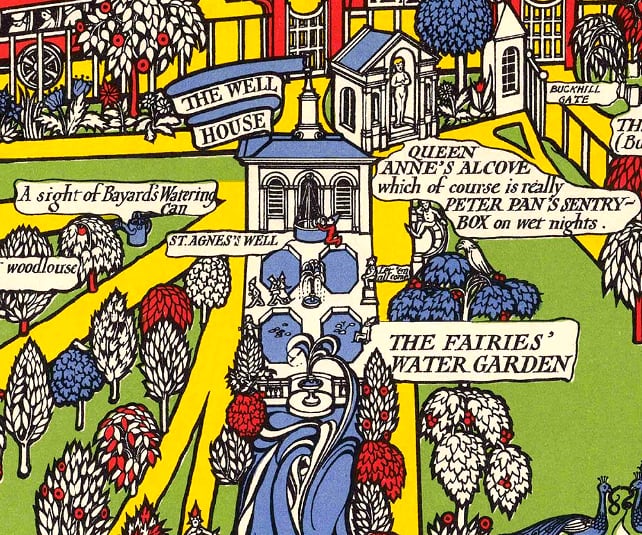

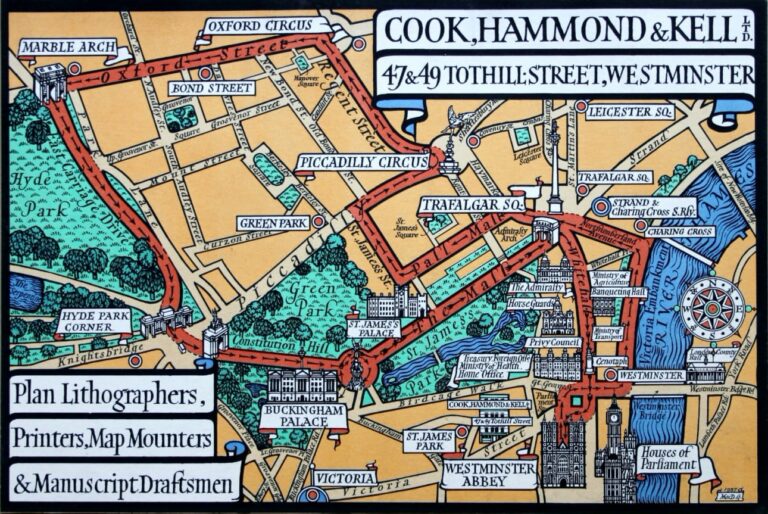

Max was not asked to design the map for the official Exhibition Guide – this commission was given to Kennedy North. However, Gerard Meynell, the original printer of Max’s Wonderground Map of London Town (1914), always eager to seize an opportunity, published a smaller folded version of this, complete with a decorative envelope. The new border – presumably amended by Max – begins: ‘The Heart of Britain’s Empire Here Spread Out For Your View …’ and on the Harrow Road a lion (the emblem of the Wembley Exhibition) was added above and arrow pointing ‘ON TO WEMBLEY’. Although thousands of copies were sold, making a tidy profit for the printer, Max would not have received royalties as Meynell owned the copyright.

Max’s work for Staples & Co helped to make the firm (and its location) a household name. He described it as:

‘the designing of some permanent advt. [advertising] vitreous enamelled panels

– 17′ x 10’6″ [5.2 x 3.2 m]

– (eight such areas + other lettering 100ft x 5 ft) all in colour, chiefly white lettering & coats-of-arms in red

– all to go on a building ½ mile outside Wembley – this used as a guide by Government literature as “where to turn off Edgware Road to the exhibition site”.’

This eye-catching signage would embed Staples Mattress Corner in the psyche of motorists navigating this part of north London and although the factory closed its gates in 1986, the name Staples Corner persists in the name of the new retail park here.

The owner of Staples, Harold Heal, brother of Ambrose, the influential designer and managing director of Heal’s furniture store in Tottenham Court Road, had also commissioned Max to build a house for him at Netherfield, East Sussex. This was completed in 1926 (see Newsletter Spring-Summer 2021).

It is with great sadness that I have to report that Oliver Heal died on 23rd February this year. He worked his way through the ranks of the family firm and was the last member of the Heal family to serve as Chairman of the company. He gained a PhD in furniture history and spent his last decades researching the history of his grandfather and his company; in 2014 this culminated in the publication of a magnificent volume: Sir Ambrose Heal and the Heal Cabinet Factory 1897 – 1939. Oliver was a true gentleman: kind, modest, hospitable, and always generous with his time. His help was invaluable in my research into Max’s work for Ambrose Heal at the Tottenham Court Road store and his home at Baylins Farm, where Oliver himself came to live in 2000. He will be greatly missed by his wife Annik, his family and friends.

University of London map. In January this year I was contacted by Professor Bill Sherman, Director of the Warburg Institute, which is based at Senate House (pictured right), the administrative heart of the University of London. He had been researching this iconic building and its architect Charles Holden and had put together a fascinating display of designs, scale models and archive film. Bill was curious to know more about the large map Max had painted for the Chancellor’s Hall. The building was completed in 1937 and the map was commissioned by Holden the following year. Priscilla accompanied Max to their first meeting but became frustrated when Holden ‘took us all over the building . . . except the big room where the map is to go which rather seemed to take the sense out of the visit. We talked of anything & everything but business’. This would have mattered little to Max who, as an architect himself, would have relished the opportunity to see round this impressive building – the tallest in London at that time, higher even than Holden’s other recent creation – 66 Broadway, the headquarters of London Underground. Later Max told Priscilla: ‘The building is very interesting, but I think he [Holden] breaks up the spaces too much – not fussy detail . . . but smallish panels with very deep mouldings.’ The map was not, apparently, urgent – a small preliminary design was only produced in June 1939.

University of London map. In January this year I was contacted by Professor Bill Sherman, Director of the Warburg Institute, which is based at Senate House (pictured right), the administrative heart of the University of London. He had been researching this iconic building and its architect Charles Holden and had put together a fascinating display of designs, scale models and archive film. Bill was curious to know more about the large map Max had painted for the Chancellor’s Hall. The building was completed in 1937 and the map was commissioned by Holden the following year. Priscilla accompanied Max to their first meeting but became frustrated when Holden ‘took us all over the building . . . except the big room where the map is to go which rather seemed to take the sense out of the visit. We talked of anything & everything but business’. This would have mattered little to Max who, as an architect himself, would have relished the opportunity to see round this impressive building – the tallest in London at that time, higher even than Holden’s other recent creation – 66 Broadway, the headquarters of London Underground. Later Max told Priscilla: ‘The building is very interesting, but I think he [Holden] breaks up the spaces too much – not fussy detail . . . but smallish panels with very deep mouldings.’ The map was not, apparently, urgent – a small preliminary design was only produced in June 1939.

Unusually, the map – measuring 2.4 x 3.4 m – was painted on canvas rather than wood panel. This was fortunate as it allowed the map to be rolled up and taken down to Max and Priscilla’s Sussex cottage when Senate House became the MInistry of Information during WW2. Max worked on the map intermittently in his tiny studio, sometimes going to London to make sketches of the various colleges for the many roundels on the map.

In August 1946 – despite many areas still needing work – the map was re-hung in the Chancellor’s Hall as the Princess Elizabeth was to be presented there with an honorary degree. Max’s attention was diverted to an urgent job for the Cunard liner RMS Queen Elizabeth – a painted map panel of the North Atlantic for the 1st class Smoke Room. Just days after finishing this, Max was diagnosed with cancer. He died in January 1947. So the University of London map remains tantalisingly incomplete.