The last year has been a strange one for everyone. I hope that you’ve all stayed well, had vaccinations, and coped with the several lockdowns we’ve had to endure. Inevitably the pandemic has led to the disruption of events including the small Max exhibition at West Sussex Record Office. This is now likely to take place in the autumn of 2022. Although lectures were cancelled in the first months of the pandemic, most societies and speakers discovered Zoom so I’ve been able to continue spreading the word about Max.

My biography of Max – MacDonald Gill: Charting a Life – has continued to sell well during the pandemic. Copies are still available from booksellers and my publisher or you can contact me directly by email or via the website.

In this newsletter I’m focussing on two buildings closely linked to Max that have been on the market during the pandemic: Darwell Hill, a beautiful thatched house in East Sussex and St Bartholomew’s Church in Chichester.

Darwell Hill

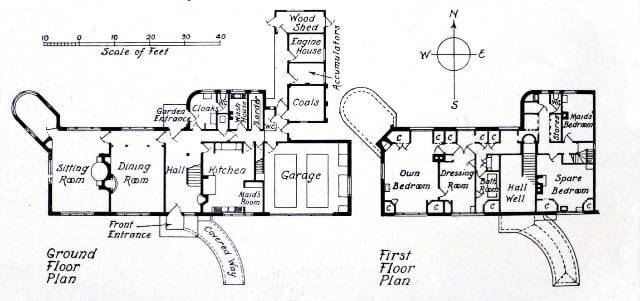

This arts-and-crafts-inspired house near Netherfield, Battle, was designed by Max for Harold Heal, the owner of Staples & Co, manufacturer of beds and mattresses. Heal’s father acquired the Staples spring patent in 1895 and founded Staples & Co to produce mattresses and beds. In 1919 he passed sole ownership of the firm to Harold – his second son. Under his leadership, Staples became a hugely profitable business. Meanwhile the eldest son Ambrose, a gifted furniture designer and astute businessman was managing the famous Heal’s furniture store in Tottenham Court Road.

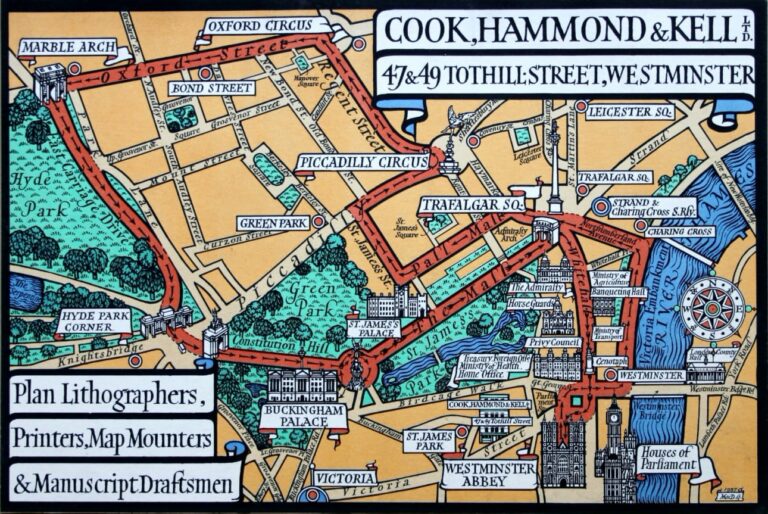

In 1924 a new Staples factory was nearing completing in Cricklewood, North London. Harold Heal commissioned Max to design the vitreous fascias – red with yellow lettering – with the Royal crest prominently displayed over the entrance. This eye-catching frontage on the corner of the Edgware Road and the A406 (soon to become the North Circular Road) led to the building’s inclusion in the official directions to the famous Wembley Empire Exhibition of 1924. The factory has long gone but Staples Corner remains embedded in the psyche of British motorists.

For his new home, Harold Heal chose a magnificent hilltop position with panoramic views towards Beachy Head and the sea. The Darwell Hill estate included woodland, and extensive gardens were created with shrubberies, a sunken garden and a water garden supplied by its own spring.

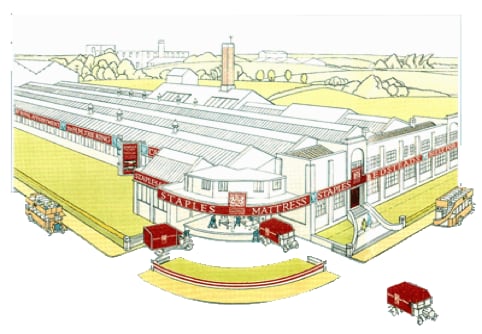

The walls of the house were constructed of small hand-made bricks with oak half-timbering set on a sandstone base. The thatched roof was made of Norfolk reed. A thatched walkway leads to the oak front door which opens onto a hall the depth and height of the house.

The house looks deceptively large. Although wide, it is only one room deep, each opening onto a narrow rear corridor. The ground floor passageway has a distinctive vaulted ceiling. Another interesting feature is the small lozenge-shaped room leading off the sitting room at the west end of the house. Darwell Hill was much admired in Country Life magazine in 1928 although the horizontally-paned Crittall windows were criticised as ‘a departure from accepted methods … and not an improvement’. It is possible they were installed at Heal’s insistence as he apparently had a strong hand in the design of the house. Heal was, by all accounts, a difficult man, and he and Max did not always see eye-to-eye: by the time the house was completed in 1926 the two were not on speaking terms.

By a feat of ingenious engineering, the spring behind the house was harnessed to provide a rather erratic flow of water while a coal-fired boiler provided the heating. It was often so cold, however, that Heal’s long-suffering wife Marjorie would resort to wearing a coat; her brother nick-named the house ‘The North Pole’.

The house was furnished stylishly but comfortably and included a dining table designed by Harold and a semi-circular desk by his brother. The original colour schemes reflected Heal’s idiosyncratic tastes. He refused to have green in the house but used blue – his favourite colour – almost everywhere including the wood floors, carpets, lamps, curtains, kitchen floor tiles, even the bathroom suite.

The Heal Rolls Royce (photo courtesy of Oliver Heal)

Marjorie Heal was the aunt of the writer John Mortimer. He often stayed at Darwell Hill as a boy. His memoir Clinging to the Wreckage contains hilarious descriptions of his eccentric uncle and his home.

St Bartholomew’s Church, Chichester

In 1919 when Max’s work on the Bladen Estate in Dorset came to an end, he moved – with his growing family – back to Chichester where he’d lived as a boy. He bought West Lodge, a detached house in the heart of Chichester, almost opposite the Cathedral. Although there were numerous churches within the city walls he chose to worship at St Bartholomew’s, a small church just beyond the Westgate in Mount Lane. He became a church warden and member of the Parish Council.

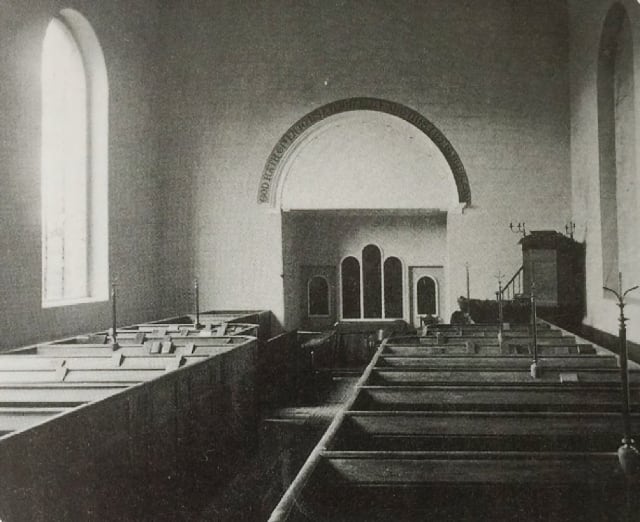

St Bartholomew’s – a Grade II listed building – stands on the site of a Norman church destroyed by the Parliamentarians in the English Civil War. It was rebuilt in 1830 by George Draper (a Chichester architect better known for his Methodist churches) in neo-Georgian style with a short tower at the west end. By the 1920s, however, the tower was unstable so Max was asked to draw up plans for its removal as well as for the addition of a chancel and adjoining sacristy. Several years of fund-raising ensued before the works were finally carried out in 1929.

After the structural works were complete, the interior was redecorated in arts-and-crafts style. The timber panels of the chancel ceiling were painted in lapis blue with gold stars and floral borders with the initial letters of the church’s name spelt out in gold leaf. The window recesses in the nave were also painted in blue with gold edging. According to a priest visiting in around 1929, Max’s original scheme was to make the entire church ‘a blaze of colour’ but this was never completed.

Max also designed new furnishings. These included a tall panelled reredos with a carved and gilded top panel, a set of altar candlesticks as well as carved and gilded prayer desks. The church’s final incumbent – evidently a puritanical type – disliked the decorations so much he had the blue paintwork in the nave window recesses obliterated with white paint. Mercifully this ‘act of vandalism’ (as the Principal of Chichester Theological College called it) did not reach the chancel ceiling.

St Bartholomew’s Church closed in 1959 but was then used as a chapel by the Theological College until its closure in 1991. From 2005 to 2018 it was leased by Chichester College for use as a chaplaincy centre and drama studio. Two years later the diocese decided to sell the building and it was put on the market with Spratt and Son with a price tag of £500,000. I understand an offer has been received from a local dance school. Local residents are naturally concerned about possible alterations to this listed building. I’ll keep readers updated.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this newsletter. Till the next . . .

My best wishes

Caroline